Texture-Based Composition: Prioritizing Timbre

Learn to use texture as a compositional tool.

Instead of focusing exclusively on chord progressions and harmonies, texture-based composition looks at sonic character and the perception of sound.

In this Article:

Texture-Based Composition

Although traditional aspects such as melody, harmony, and rhythm are foundational in music composition. These are not the only ways to create music. When the timbral quality of each sound becomes more than just a novelty in music, we can look at the emotive effect of this over the duration of the performance or piece.

Here, elements such as density, ambience, spectral content, motion, transformation, and noise become tools we can use to shape and contextualize sounds. If you’d like to find out more about the origins of this approach to music creation, be sure to explore electroacoustic music movements like Musique concrète (France) and elektronische Musik (Germany), as well as minimalistic and experimental styles like ambient and drone.

Texture-Based Composition: Using Texture as the Primary Focal Point

In traditional music theory, sonic texture is often characterized using terminology such as monophonic, polyphonic, or homophonic. When we focus on texture in composition, however, we look more closely at the behaviour of sound elements and their interactivity over time within the frequency spectrum.

An essential concept to understand is that harmonic density does not necessarily equate to textural density. There can be more textural complexity in a single layer of white or pink noise with a moving low-pass filter than in an elaborate chord progression. When we analyze the texture of a sound, it’s important to consider:

- Density: Is it sparse or busy?

- Activity: Is it static or constantly moving?

- Spectral balance: Is it tonally dark or bright?

- Coherence: Are the layers blended or separated?

When we listen to sound, we experience these dimensions of texture holistically rather than analyzing them on a note-by-note basis. This makes our approach more perceptual than theoretical, which is another key aspect from a philosophical point of view. In practice, there is a major reliance on real-time listening and adjustment, instead of planned sheet music arrangements.

Texture-Based Composition: Constructing Textures

When we think texturally, the roles that instruments play within a piece of music change. For example, a hi-hat pattern can work more as a noise bed in the high frequency range than a rhythmic element, while a Lo-Fi vocal sample stab becomes a grainy pad instead of a lyrical statement. Working with textures starts with the selection of our sounds, so recording techniques, synthesis, and processing are crucial.

Sounds like cymbals, noise, and ambient recordings occupy a large part of the audible spectrum, so these can become powerful tools, especially if altered and shaped over time. Meanwhile, the more narrowband elements, like sine waves, can be layered, modulated, or reverberated to create more texture. Repetition can also play a role, as short loops with subtle variation create momentum.

By using incremental layers, we can build layers that complement and reinforce each other across the spectrum. In the lows, a drone can add to the scale and weight of a sound, while the midrange is ideal for introducing movement and complexity. At the same time, high-frequency content adds detail. What’s key here is that not every layer needs to be heard simultaneously. Instead, some can be felt, which is less obvious and adds to the immersive feel of the composition.

Luckily, this production approach suits many of the plugins, hardware instruments, and effects available in today’s music tech landscape. Samplers, loop stations, and pedals like the Hologram Electronics Microcosm and the Chase Bliss Mood can quickly transform sounds into soundscapes. As a composer, your job then becomes continuous curation and shaping of the processing rather than simply deciding which notes to write.

Texture-Based Composition: Shaping Texture over Time

Instead of relying on dramatic chord changes, texture-based music needs sounds to morph and change. However, the arrangement dynamics technique of contrasting sparse passages with dense sections is still effective. You can build these changes gradually over a few minutes or create sudden, unexpected shifts that keep the audience on their toes.

Processes like amplitude modulation, filtering, or changes in density can cause sounds to evolve texturally, especially if done slowly. These can become compositional tools, as a sound can become brighter, more complex, or thinner and fade out. Because these processes take time to execute, they encourage active listening, which in turn allows you to use more detail as a composer.

In the context of texture-based music, form is often a fleeting and emergent characteristic instead of being predefined. While traditional songs use rigid verse/chorus patterns, texture-based pieces can be arranged according to more abstract guidelines like states of animation or environmental zones. This allows movement between sparse and dense sections, as we mentioned, animation and stillness, or clarity and saturation. The transitions between these characteristics become like cadences and progressions.

These techniques are particularly interesting in the context of live electronic music performance. Working with sounds over a long period of time, like a sculpture, plays with the audience’s focus and perception.

Texture-Based Composition: Spatial Texture

The ability to manipulate sound from a spatial point of view is a key aspect of texture-based music. With effects like delay, reverb, and stereo imaging, we can change the way the listener experiences a certain texture. The feel of a distant sound echoing at the back of the mix is so different from when it’s dry and pushed forward, even if the source is identical.

For this reason, the placing of a sound within a sonic environment is not finite in texture-based music. We can layer multiple spatial effects with contrasting sound envelopes, frequency ranges, and stereo imaging to construct intricate and vast soundscapes. Instead of being simple rhythm tools, delays become like a sonic paintbrush for diffusing and blurring transients.

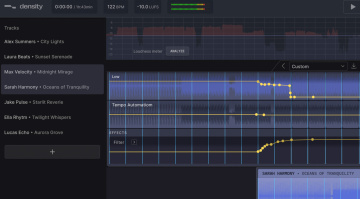

Controlling dynamics carefully is also a key part of creating depth. This allows us to create organic tidal motion or breathing, as textures bloom forward and retreat back into the mix. By automating effects sends, wet/dry mix controls, filtering, as well as stereo width and panning, we can lightly alter spatial characteristics over time to create a more immersive listening experience.

Whether you’re listening to a live performance or a record, spatial texture is crucial in how it translates across different playback systems. Because you are perceiving one sound in relation to another, it’s more likely to translate well compared to a sound with finite spatial character.

Texture-Based Composition: Creative Decision-Making

With fewer discernible musical events and mostly subtle changes, texture-based music requires a different approach from the listener. This means that, as composers, we need to train our perception to recognize micro-variation. Although it may not seem so at first, making minor tweaks to controls like modulation depth or noise filtering can really enhance the impact emotionally.

As a composer, your intent becomes critical, and having well-formed concepts for songs becomes the point of reference as you create. It can also be helpful to think of yourself guiding the listener through the sonic environment you’re creating and changing, as this creates a narrative that reinforces your decisions.

Restrictions can become catalysts in the creative process. By limiting the number of sounds or effects channels and tightly controlling the frequency range of each sound, the transitions come across more boldly. Rather than using a myriad of ideas, texture-based music shows us how to get the most from a single sound source, treating it like a dynamic and multi-faceted solo performance.

More about Texture-Based Composition:

*Note: This article contains affiliate links that help us fund our site. Don’t worry: the price for you always stays the same! If you buy something through these links, we will receive a small commission. Thank you for your support!

One response to “Texture-Based Composition: Prioritizing Timbre”

4,5 / 5,0 |

4,5 / 5,0 |

= basic principles of orchestration.

This is why studying music theory counts.