Uncompressed Audio Formats: Is “High-Quality” just a Myth?

We discuss the purposes of high-quality uncompressed audio and whether it actually makes a difference to the average listener on music platforms.

In this Article:

When we enter music production and audiophile circles, we’re immediately confronted with a deluge of opinions, including the claim that uncompressed audio offers a superior listening experience. While professional recording studios usually record at sample rates of 96 kHz, audiophile listeners in the hi-fi realm swear by formats like WAV and AIFF.

This topic continues to be debated in online forums, so we’re looking deeper to find out if so-called high-quality uncompressed audio is noticeably discernible to the average listener—or is it simply a rather niche interest, a mere myth perpetuated by manufacturers of high-end audio gear?

Compressed vs. Uncompressed Audio

Because digital audio files are stored like any data on your hard drive, we use different types of data compression to reduce the size of files, while preserving the audio quality as much as possible.

Formats such as MP3, AAC, and OGG are regarded as lossy compression algorithms because the process actually discards parts of the original audio file that aren’t immediately recognizable to the human ear. As a result, these file formats are highly economical when it comes to storage space, but there is a loss of detail, particularly in the extremities of our hearing range.

At lower bitrates, the degradation will be immediately apparent in the ultra-low and ultra-high frequency ranges, close to 20 Hz and 20 kHz.

Alternatively, there are formats like FLAC (Free Lossless Audio Codec) and ALAC (Apple Lossless Audio Codec) that preserve the full integrity of the original audio while reducing the file size. Rather than discarding data, these lossless compression algorithms use predictive modeling, which isolates and removes redundancies and repeating patterns within the audio.

Meanwhile, WAV, AIFF, and PCM are known as uncompressed formats because they maintain the entirety of the audio data without reducing the quality. Although the file size is larger, the fidelity is maximized, which is why they are the standard for pro audio.

| Compression | Format | File Size per 3-min song | Quality | Uses | Listening Experience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncompressed | WAV, AIFF, PCM, BWF | approx. 30 MB | Same as original | Recording, mixing, mastering, archiving | Identical to source. Sounds the same as lossless on most consumer devices. |

| Lossless | FLAC, ALAC, APE | approx. 15 MB | All data perfectly reconstructed, but smaller size. | Music libraries, high-quality downloads, audiophile listening | Virtually indistinguishable from uncompressed audio to most listeners. |

| Lossy | MP3, AAC, OGG | approx. 3 – 6 MB (bitrate dependant) | Portion of data discarded, loss of detail at low bitrates | Streaming, portable devices, casual listening | At high bitrates (256–320 kbps), differences are hard for most listeners to hear. |

The Advantages of Uncompressed Audio

As we’ve touched on briefly, the primary benefit of using uncompressed audio formats is that there is no loss in detail. You’ll immediately notice these nuances in aspects like reverb tails and cymbal decays when you compare a professionally recorded, mixed, and mastered WAV file to a 128 kbps MP3, and this is quite an easy test to do with one of your favourite songs.

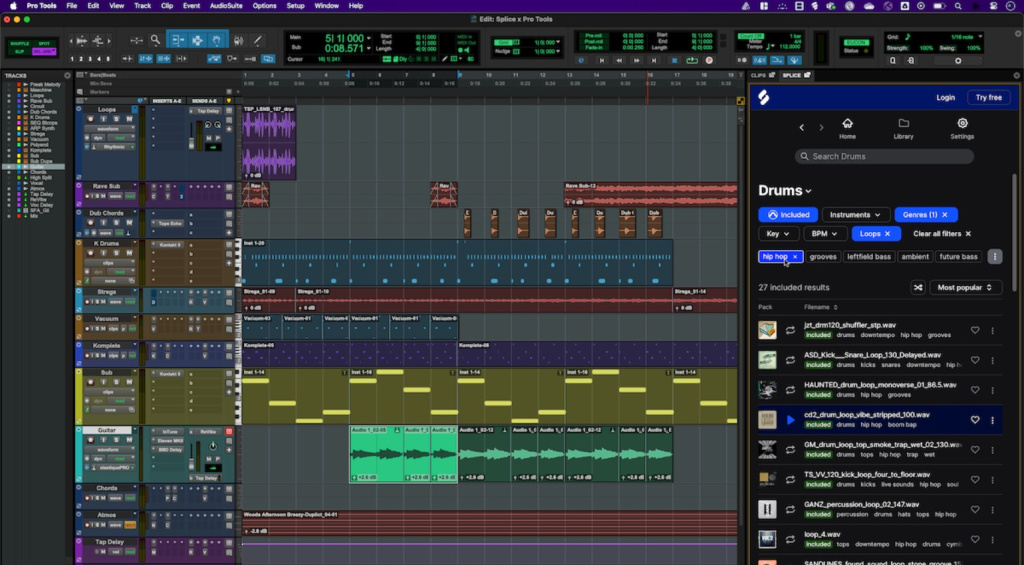

In a DAW, the flexibility we have with non-destructive editing when working with uncompressed audio files is phenomenal. Because we have the best possible representation of the source sound, we can trust that the integrity is preserved with any processing we add. Another aspect is the compatibility of WAV and AIFF, as you can easily import them into any DAW.

Furthermore, if you’re looking to archive any kind of recordings, using uncompressed audio makes it easy to catalogue and you future-proof your data with the highest-quality files if new standards come into play in the future.

Uncompressed Audio: Can You Actually Hear the Difference?

In the pro audio realm, the advantages of using uncompressed audio formats are self-evident for the most part. However, the argument truly arises when it comes to listening. Is it truly possible for a listener to discern between an uncompressed audio file and a compressed one?

According to most of the studies and blind tests demonstrated online, it’s really difficult, even for a professional mastering engineer, to tell the difference between a decent quality (320 kbps) MP3 and a WAV file. Naturally, the sonic environment and the playback system play a role, so it’s harder to distinguish the subtle differences on most consumer devices.

Then there’s good old confirmation bias. The expectation that uncompressed formats sound better can affect the perception of any user trying to do an honest test. To sum up, there’s no denying the technical superiority of uncompressed formats, but the context really does matter. Don’t be the one raging in forum debates when you mostly listen on laptop speakers.

Uncompressed Audio: Where does High-Quality Audio really Count?

OK, so maybe the average consumer can’t tell the difference. Are there still situations where uncompressed audio really counts?

- Recording & Mixing: Unless you specifically desire the Lo-Fi sound of an old TASCAM 4-track, introducing more hiss with every overdub, you need to use uncompressed digital audio to maintain the highest possible fidelity.

- Critical Listening: If you’ve customized and acoustically treated your listening environment, you’ll be able to get the most out of your high-end audiophile equipment, to truly observe and enjoy the difference between vinyl, cassette, and digital formats.

- Archival Purposes: Once an audio file has undergone data compression, the resulting audio can’t ever be restored to the quality of the original. This is why using uncompressed for the archiving of master recordings is essential, so nothing gets lost.

On the contrary, though, when it comes to streaming music to the masses on a daily basis, there is no denying the convenience of using data-compressed formats like MP3 and OGG.

Uncompressed Audio: Bit Depth and Sample Rate

If CD quality is 16-bit 44.1 kHz, why would I ever need to go beyond that? Well, in the context of an analogue-to-digital conversion, the sample rate determines how many times per second the audio is being converted. This means that higher sample rates (96 kHz and above) provide greater detail, even if our ears can’t tell the difference between a 96 kHz and a 192 kHz recording in the moment.

On the other hand, the bit depth is closely linked to the dynamic range, so 16-bit means roughly 96 dB of dynamic range, and 24-bit equates to around 144 dB. This is why we use 32-bit floating point systems for recording, as this negates the possibility of clipping and noise, and offers the most flexibility in post-production.

Overall, high sample rates and bit depths might matter in the music production process, but they do far less when we are listening to music in our daily lives.

More about Uncompressed Audio:

*Note: This article contains affiliate links that help us fund our site. Don’t worry: the price for you always stays the same! If you buy something through these links, we will receive a small commission. Thank you for your support!

3,1 / 5,0 |

3,1 / 5,0 |