Music Theory for Producers: Write More Compelling Music

An introduction to some of the key Music Theory aspects for Music Production.

We dive into music theory for producers and tackle some of the foundational aspects that can become tools to write more compelling music.

In this Article:

Music Theory for Producers

If you’re a self-taught music producer, the theoretical side of music can seem foreign and counterintuitive to your creative process. However, with a basic understanding, we start to see music theory as a tool set that can help us reduce even the most complex musical passages into a group of patterns. The more we learn, the easier it is to recognize relationships between musical elements.

As you start to use music theory deliberately, you’ll see that it provides a creative framework with a set of rules that can be bent or broken to suit your composition style. If you’re creating beats and building arrangements in your DAW, you’re already using music theory to an extent. By using theory to your advantage, you can go beyond trial and error and compose music intentionally.

In this workshop, we’ll cover five essential aspects of theory that you can immediately apply in your music production process. However, it’s important to remember that instead of striving for an external idea of perfection, you are simply looking to make your music more impactful on an emotional level.

Music Theory for Producers: Scales and Keys

All music can be broken down into a group of notes that provide context within the 12 tones of Western music. These tones repeat throughout our hearing range in spans of notes called octaves, in which we use 7-note patterns called scales to distinguish one piece of music from another. In practice, this means that the scale we’re working in determines the key of our composition.

If we’re working in A minor, for example, our bassline, chords, and melodic parts are created predominantly with the notes A, B, C, D, E, F, and G, and the lowest note most frequently used will be A, which is also referred to as the tonic. As we ascend in a scale from any note, the third note in the sequence defines the scale as either major or minor.

- Major: Predictably bright (third note is a whole step or whole tone above the second)

- Minor: Dark and mysterious (third note is a half step or semitone above the second)

Although the contrast between major and minor is stark and easily recognizable, the actual difference is very slight, which means that three semitones below the tonic of any major scale, we find its relative minor scale that uses the exact same seven notes. This relationship is crucial because it allows songwriters to use the ambiguity to create emotional dynamics.

Another variation of a scale, which is important to understand, is called a mode. Derived from a major scale, modes have unique qualities that can expand the emotional palette of a musical composition. Like major and minor scales, modes can use any note as the tonic center, which is called the Final within a mode.

There are seven basic modes (known as authentic modes), which have distinct characteristics. In some modes, certain notes have been raised or lowered by one semitone from their positions in major or minor scales.

- Ionian: Identical to a major scale (Nursery Rhymes)

- Dorian: Minor scale with raised 6th (Blues and Funk)

- Phrygian: Minor scale lowered 2nd (Heavy metal, Flamenco, and Film score)

- Lydian: Major scale with raised 4th (Jazz and Prog Rock)

- Mixolydian: Major scale with lowered 7th (Blues and Rock)

- Aeolian: Identical to natural minor scale, i.e., not harmonic or melodic (Classical)

- Locrian: Minor scale with lowered 2nd and 5th (Jazz, Musical Transitions)

Tip: To put this understanding into practice, try creating three different music loops with the same drum beat. Write the melodic parts or basslines for one loop in a major key, one in a minor key, and one in a mode, and see how they compare from an emotional standpoint.

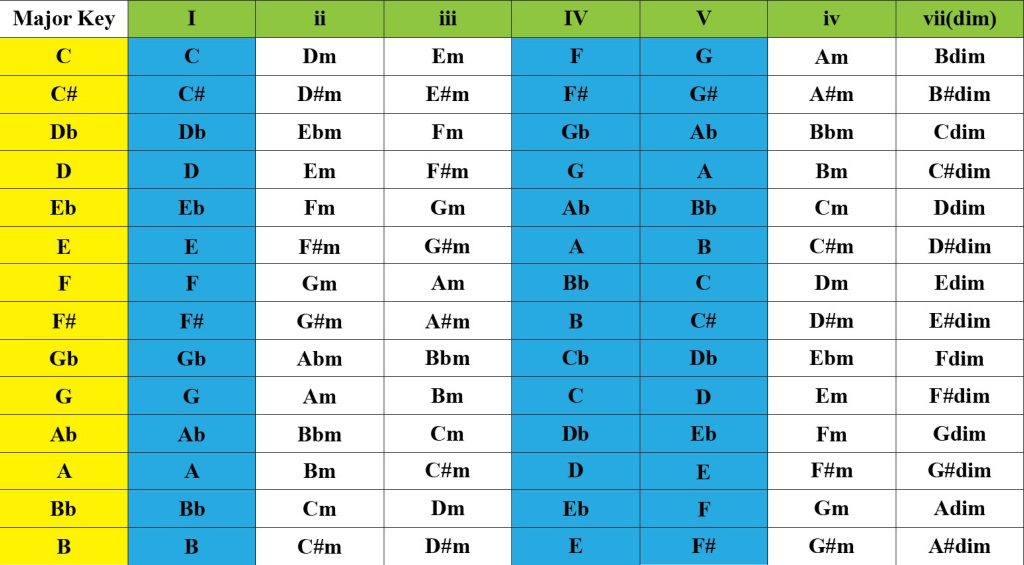

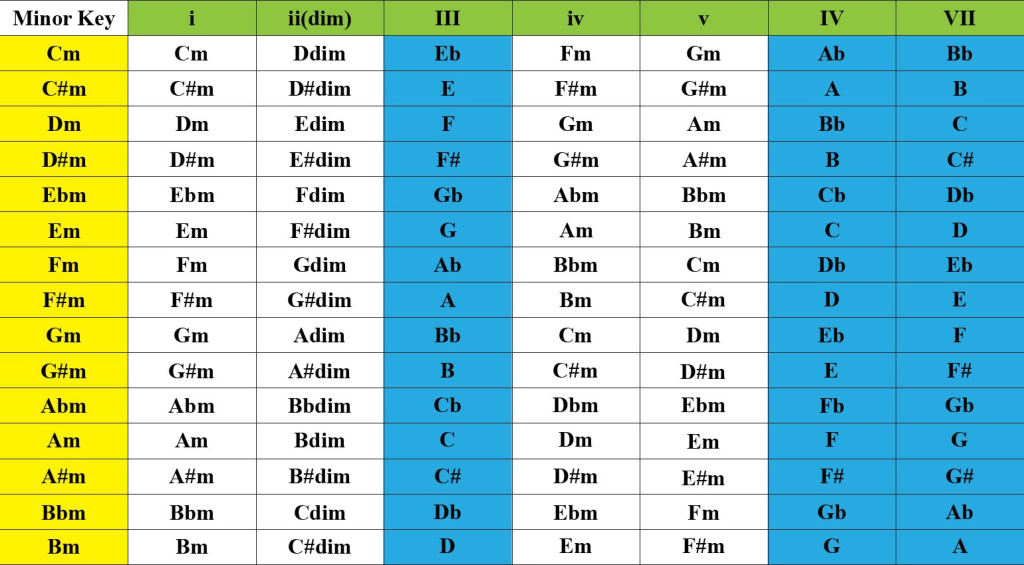

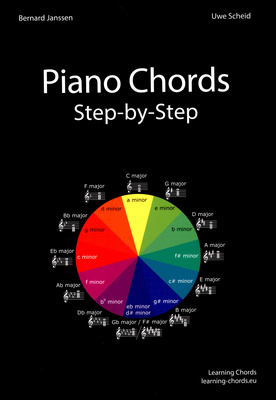

Music Theory for Producers: Chords and Harmony

When we play more than one note at a time, we create a chord, which is a building block of harmony in music composition. In their most basic form, chords are known as triads consisting of three notes. However, the notes in any triad can be reordered and voiced in different octaves to provide more variation and musical depth. These chord variations are known as inversions.

- Major chords: To create a major triad from any note, add two notes four and seven semitones above it. (Bright and balanced)

- Minor chords: To create a minor triad from any note, add two notes three and seven semitones above it. (Dark and moody)

- Sevenths and extended chords: For a more complex, sophisticated chord, we can add the 7th note of the scale to any major or minor triad.

Things start to get interesting when we arrange different chords in a sequence called a chord progression. This introduces multiple changes in harmonic intervals, which creates an emotional storyline or arc to build your song around. When we look into different eras and styles of music, we find signature progressions like I-IV-V in pop music or ii-V-I in jazz.

Using chord progressions enriches your production, and you can do it with pads and arpeggiations, as well as stacked vocal samples, which can be used to suggest chords. Be sure to throw in an inversion every now and again to add anticipation to a transition. What’s more, you can create a surprise moment by using a chord from a different key (non-diatonic chord).

Tip: Try creating a three or four-chord progression in your DAW, and then dragging the MIDI onto a different software instrument track to see how the same chords transform when they are played by a piano, a synth or string pad, or a guitar. Also, add expression by playing rolled chords, where you don’t hit all the notes of the chord at once.

Music Theory for Producers: Rhythm and Groove

Having a distinctive and unique rhythm track can be the difference between a timeless hit song and millions of unremarkable others. Understanding rhythm goes beyond the quantization grid setting in your DAW, and it can help us create more expressive music and insert energy into transitions to elevate the feel of the song.

- Meter: Most modern music uses a 4/4 time signature, but you can shift the feel by working in half time, like in trap music.

- Subdivisions: You can explore different note lengths and timings by adjusting your MIDI grid from quarters to eighths, sixteenths, and triplets.

- Syncopation: In genres like hip-hop and house, placing the emphasis on the off-beat adds momentum to the groove.

- Polyrhythms: By laying two rhythms with different meters or pattern lengths, we can create tension and build anticipation.

Another side of groove comes from the natural variation of human playing or microtiming, which can push or pull beats and give them a lively feel. In your DAW, you can simulate this with the help of groove templates that add swing in different degrees, or you can individually nudge your drum hits ala J. Dilla.

Tip: Try programming a simple hi-hat loop and nudging every second note forward slightly. Notice how the beat seems to have more urgency suddenly? Meanwhile, with basslines, you can program your rhythm on one note before adding variations. Listen to how it adds weight to the track without complicated harmonies.

Music Theory for Producers: Melody Writing

By combining catchy rhythms and note intervals, Melody is the single aspect that can make your song more memorable. When we take a closer look, a good melody has a balance of variation and repetition, usually with a main motif that leads the composition smoothly into the verses or chorus while moving slightly here and there as the chord progression follows.

These small changes prevent the composition from becoming stagnant and predictable. Using smaller intervals or stepwise motion, we can give the melody an organic feel similar to vocals. Meanwhile, larger intervals expand the emotional dynamics, giving the melody a sense of space.

However, it’s important to remember that melody is all about context. In more minimalistic forms of dance music, the only melodic element is a simple ostinato, consisting of five or six notes. Through clever sequencing of the other elements in the song and using time-based sound design (automation), electronic musicians create hypnotic grooves that vary just enough to keep you on the dance floor.

A composition can feel more grounded when the melody resolves to the tonic. However, by delaying the resolution, we can build tension and intrigue. In some cases, the melody never resolves by design, like Hans Zimmer’s iconic theme from Sherlock Holmes.

Tip: Try building a melody with just three notes from the scale you’ve chosen. Once you’ve got the rhythm pattern locked, add variation with close intervals and some larger ones. By purposefully limiting your options, you can actually create stronger melodic ideas. Using layering of octaves, sixths, or thirds can really expand your main hook, making it the feature of your song.

Music Theory for Producers: Tension and Release

By deliberately introducing tension and releasing it at the right moment, you can keep your listeners hooked and coming back for more. With some music theory knowledge, we can use specific harmonies and intervals to build tension during drops and pre-choruses.

- Dissonance: Intervals with an unbalanced frequency ratio, like sevenths or seconds, introduce tension.

- Consonance: Balanced interfaces such as thirds, fifths, or octaves can be used to resolve tension.

- Dominant–tonic movement (V–I): By moving from the fifth to the first chord, we can use one of the signature resolutions in Western music. To gain more understanding about this, read about cadences.

In composition, we can apply this by using dissonant chords or melodic parts that resolve downward to anticipate musical transitions. Meanwhile, dense rhythmic layers can create metric dissonance, which we can resolve by simplifying the arrangement. For the finishing touches, using sound design elements like white noise and filter automation can emphasize the tension in an atmospheric way.

Tip: To start off, try creating a build-up over eight bars using a single chord and increasing the complexity of the rhythms, opening the filter cutoff, and introducing tense intervals. Then, at the drop, resolve with a simple stable chord.

| Topic | Example | Application |

|---|---|---|

| Major Scale | C–D–E–F–G–A–B (formula: W–W–H–W–W–W–H) | Brighter, more uplifting progressions |

| Minor Scale | A–B–C–D–E–F–G (formula: W–H–W–W–H–W–W) | Darker, more emotional passages |

| Modes | Dorian: D–E–F–G–A–B–C (funky) Mixolydian: G–A–B–C–D–E–F (bluesy) Phrygian: E–F–G–A–B–C–D (dark, exotic) | Use to change tonal colour |

| Chords | Major (C–E–G) = happy Minor (A–C–E) = sad 7th (C–E–G–B) = jazzy sus2/sus4 = suspended, unresolved | Build harmony with synths and guitars |

| Progressions | I–V–vi–IV (C–G–Am–F) – pop/EDM ii–V–I (Dm–G–C) – jazz/R&B vi–IV–I–V (Am–F–C–G) – emotional pop/rock | Emotional templates/starting points for tracks |

| Intervals | 3rd = smooth 5th = stable, strong 7th = tense Octave = powerful doubling | Basslines and melodies |

| Rhythm | 4/4 = common time 3/4 = waltz feel Syncopation = off-beat accents Swing = uneven subdivisions | Humanize your beats |

| Tension | Dissonance = minor 2nd, tritone Resolution = major/minor 3rd, perfect 5th Dominant → Tonic (V → I) = classic release | Create emotional dynamics |

| Basslines | Follow chord root note Add passing tones Sync rhythm with kick drum pattern | Grounds harmony and groove |

More about Music Theory for Producers:

*Note: This article about Music Theory for Producers contains affiliate links that help us fund our site. Don’t worry: the price for you always stays the same! If you buy something through these links, we will receive a small commission. Thank you for your support!

4,3 / 5,0 |

4,3 / 5,0 |