The Birth of the Fairlight CMI – When Computers Took Over Music

Since I first saw it demonstrated on the BBC TV programme ‘Tomorrow’s World’ in 1980, I have been fascinated and obsessed with the Fairlight CMI, a remarkable machine that changed the way we make music and whose DNA remains in the way we use computers in music to this very day.

Its inventors should, in my very humble opinion, be held in the same regard as Bob Moog, Tom Oberheim, Dave Smith, Ikutaro Kakehashi, et al, such was their impact on the way we make music and how it shaped modern culture.

Since 2013, I’ve been involved with restoring and repairing Fairlight CMIs and have become somewhat intimately knowledgeable about them. I’ve also been incredibly fortunate to meet and befriend its inventors and many of the people who brought this game-changing instrument to life.

The Birth of the Fairlight CMI

The 1980s have been called many things by many people. “The Decade That Style Forgot” is a favourite, although in my very humble opinion, as someone who lived through the decade as a teenager and beyond, I thought we were VERY stylish!

But that’s another story. However, one thing that CAN be said of that decade is that it was one of great innovation and technological revolution. It was the decade where computers became household objects, and the future really felt like it was up for grabs.

And it was the development of one computer in particular, in Australia, that would change the way music is made to this very day. Born out of the desire to create acoustic sounds using electronics, the Fairlight Computer Music Instrument, or Fairlight CMI for short, would be ground zero for almost every facet of modern music technology that we use today. But how did it achieve such a status?

Humble Beginnings

The Fairlight CMI’s story began in the basement of the house belonging to one of its co-inventors, Kim Ryrie. Ryrie had enlisted the help of his school friend and a dangerously curious guy called Peter Vogel. Their plan was to create an instrument that could authentically reproduce acoustic sounds using electronics. This was the goal of most synth manufacturers of the day.

Look at any analogue synthesiser during the 1970s, and most would have settings or patch sheets named after trumpets, violins or oboes. But try as they might, using additive synthesis, they kept coming up short, unable to create and process harmonic tones well enough to deliver what they wanted to hear.

Tony Furse

Coincidentally, in Australia’s capital city, Canberra, Tony Furse was trying, and failing, to do the same at the Canberra School of Music at ANU. As it happened, Tony worked for RCA and had access to the then-new Motorola 6800 CPU. He decided this was the way forward and developed his QASAR Multimode 8 (aka the M8).

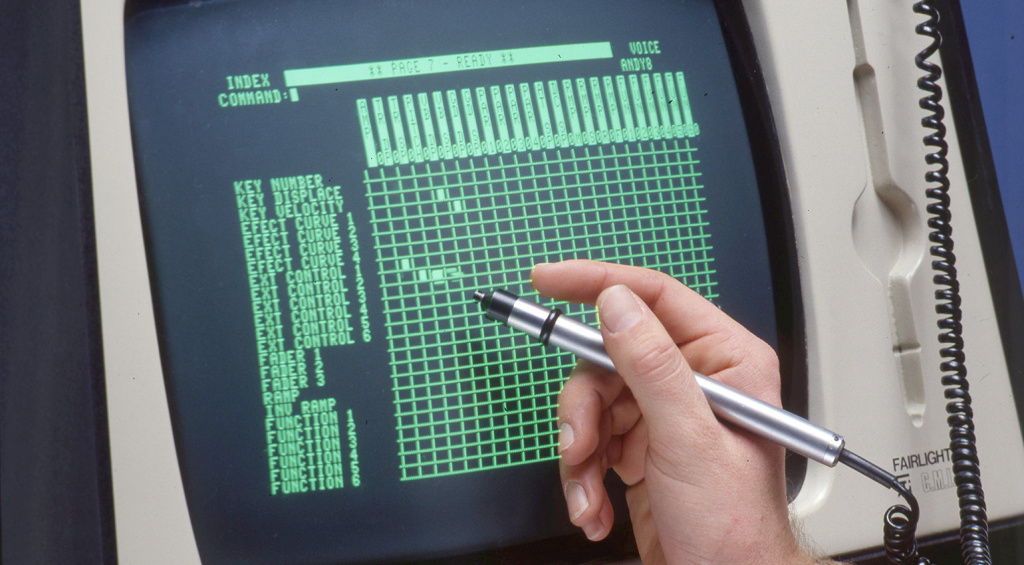

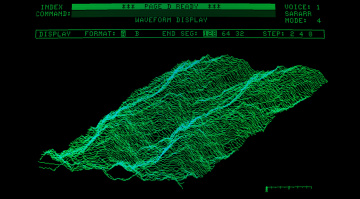

A veritable birds nest of wire wrapping and no PCBs, it began to show signs of promise and utilised a very modern CRT monitor and light pen to draw harmonic waveforms and used Fast Fourier Transform to try and get those elusive sounds.

But it wasn’t happening, at least not on a commercially viable level. Vogel & Ryrie got wind of Furse’s work, drove down to Canberra from their Sydney base, liked what they saw and licensed the tech to see if they could take it further. Soon, the M8 became the QASAR CMI, the wire wrapping replaced by custom-built PCBs, set out in a modular fashion, each with a specific task.

Tony’s contribution is often left out of the telling of the history of the Fairlight CMI. Whilst his association with the machine that went on to become the digital sampler we all know and love ended before it took over the world, he remains an essential and important part of its development.

Sampling. Was it Cheating?

Despite refining Tony’s work, they were still unable to make anything sound authentic enough. Until one day, exasperated by their persistent failure, Vogel wondered if he could convert analogue sound into digital data, store it in RAM and then play it back via a keyboard.

Building his own ADC/DACs, his initial experiments yielded not only success, but also delivered a very passable recreation of the sound fed in. Little did he know that he had just created digital sampling and that he and his creation were about to change the world.

Feeling like a cheat, he showed his discovery to his partner, and they decided to run with it. Development continued apace until November of 1979, when the first Fairlight CMI, the Series I, was unveiled to the world at various shows such as AES and NAMM. Such was their sense of cheating, they even told reps not to mention the “sampling bit”!

As luck would have it, or maybe not, Elvis died just two years previously, and a member of his band and fellow Aussie, by the name of Bruce Jackson, returned home looking for work. His mother, Ryrie’s neighbour, told him to check out the two guys next door as they were doing something “musical”. What he saw blew his mind, and he immediately set about getting Vogel and a functioning prototype across the Pacific to LA.

What happened next was a serendipitous and hugely fortuitous chain of events that saw the fledgling business take its first orders from the likes of Stevie Wonder, and word soon spread to the UK, courtesy of Larry Fast, where Peter Gabriel fell for this new musical tool, so much so that he set up a distribution company with his cousin, Stephen Paine.

The rest, as they say, is history. The Fairlight CMI became a household name, loved and despised in equal measure for its revolutionary sound and musical compositional capabilities, as well as the fear of making working musicians completely redundant.

Did You Know?

Not a lot of people know this, but Fairlight essentially invented MIDI before MIDI existed. To have the music keyboard ‘speak’ to the mainframe, they implemented a serial communication protocol that operated at a 9600 baud rate.

When Vogel travelled to L.A. to meet with Dave Smith and Kakehashi-san to discuss the first iteration of MIDI, he found that the method they were proposing was virtually identical to what Fairlight were already doing, just at a faster baud rate.

As a consequence of this, Fairlight’s famous Page R sequencing application became the first on-screen sequencer and would form the basis for every DAW we use today. One could argue that it was the first DAW!

Inside a Fairlight CMI

But how did it work, and what was inside that beige mainframe that turned music production on its head? Let’s take a look at the Series IIx, the most popular and influential model, given its use of MIDI and graphical on-screen sequencing via Page R.

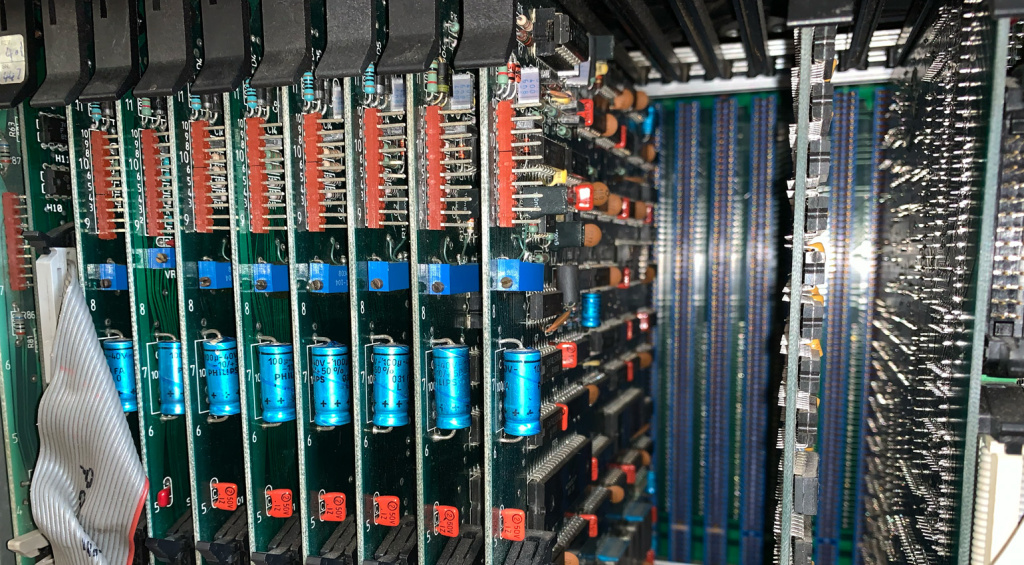

The mainframe looked like many computers did back then. A plethora of PCBs, PSU’s and various inputs and outputs, with two 8” floppy disk drives to the right, one to supply the OS and applications, and the other for loading and saving data, such as samples.

The drop-down panel at the front contained a number of CPU halt and reset switches and was opened by two catches at the top. This exposed the PSU on the left, with its huge capacitors and to the right of those, the individual function cards. From left to right, you had the following:

- 1x CMI-02 – Master Card

- 1x CMI-28 – General Interface Card (Clock/MIDI)

- 1-8x CMI-01 – Channel Card (Each with 16k Sample RAM)

- 1x CMI-07 – Analog Interface Card (Optional CV Functionality)

- 1x Q148 – Light pen Interface Card

- 1x Q256 – System RAM (256k)

- 1x Q133 – CPU Control Card

- 1x Q209 – Dual Motorola 6809 CPU Card

- 1x Q219 – Light pen/Graphics Card

- 1x QFC9 – Floppy Disk Controller

- 1x Q077 – Hard Disk Controller (Optional HDD Feature)

- 1x Q137 – Front Panel Control Card

The Music Keyboard, aside from its keyboard mechanism, had a CMI-10 Keyboard controller card, which received note on/off and velocity data from a set of three CMI-11 switch modules that held the individual key contacts.

Of course, all this hardware would be useless without software, and Fairlight employed some of the best and brightest programmers they could find, like Steve Rance, Michael Carlos and Adrian Bruce. There are many names i could mention here, but they know who they are!

The Legacy of the Fairlight CMI

All of these components, including the iconic housings, were assembled by hand in Fairlight’s facility in Rushcutters Bay, and came together to form the Computer Music Instrument, quite literally changing the way we make music forever. Both technologically and culturally important, the legacy of the CMI lives on to this day.

Thankfully, its internal design does not. It’s temperamental, fragile and becoming rarer by the day. If I had a penny for every time someone tells me that their mobile phone has “a million times more processing power”, I’d be a very rich guy. It’s true, but what your mobile device lacks is character. It lacks brazen ingenuity, unshackled by bean counters and style gurus.

Your phone doesn’t smell of warm electronics, nor does it deliver a deep sense of satisfaction every time it powers up and boots without failing. Most importantly, it is too clean. Too pristine. There’s no sonic colour or quaint glitches. It’s too perfect, and that’s what is missing in so much today. And that’s why I still love the Fairlight CMI.

More Information

- Peter Vogel’s Website

- Peter Vogel and Kim Ryrie’s NAMM Oral History

- A Fairlight CMI playlist

- Fairlight CMI history at Google Arts & Culture

- The Story of SARARR, one the most famous Fairlight CMI samples

*This post contains affiliate links and/or widgets. When you buy a product via our affiliate partner, we receive a small commission that helps support what we do. Don’t worry, you pay the same price. Thanks for your support!

One response to “The Birth of the Fairlight CMI – When Computers Took Over Music”

5,0 / 5,0 |

5,0 / 5,0 |

I watched the Tomorrow’s World clip recently, and the presenter said ‘this instrument generates computerised versions of the sounds’, which is not true. The Fairlight captures samples and replays them. What the presenter inferred was ‘resynthesis’ that takes a sample and recreates it from oscillators. But back in 1980, before sampling was widely known about, it was perhaps misunderstood. We’re only waiting for the Behringer Fairlight now at £150, rather than the £150000 of the groundbreaking original. I think the Amiga deserves a mention too, the first affordable device capable of 4 channel sampling (8 bit, initially) and playback.